The World’s Most Powerful Languages

|

What leaders should know about English and other languages competing for global influence.

Should we all emulate Mark Zuckerberg and embrace speaking Mandarin? In April this year, U.S. President Donald Trump’s grandchildren (aged 5 and 2) engaged in soft diplomacy at the highest level when they sang in Mandarin for the Chinese president and his wife. Ten years ago, investor Jim Rogers even moved to Asia to provide his daughters with a strong Chinese learning environment.

Language opens doors. Speaking more tongues means more opportunities to participate in conversations… or eavesdrop on them. It’s also clear that the power of a language goes beyond simple head count, not to mention that it’s difficult to count the number of speakers of a language given their various proficiencies. As someone who became a polyglot (five languages) in my 40s – proving that picking up languages in later years is not insurmountable – I grew interested in ranking the usefulness of languages in a scientific manner.

I created the Power Language Index (PLI) as a thought experiment: If an alien were to land on Earth, what language would serve it best? This scenario assumes that the alien would have similar ambitions as humans. For instance, it would want to avail itself of the five main opportunities provided by language:

1. The ability to travel widely

2. The ability to earn a livelihood

3. The ability to communicate with others

4. The ability to acquire knowledge and consume media

5. The ability to engage in diplomacy

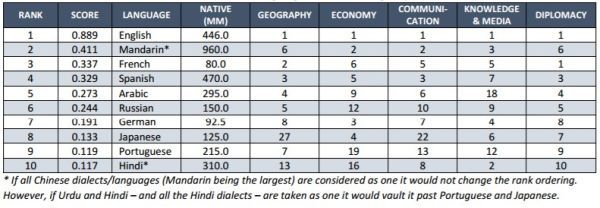

The PLI compares the efficacy of more than one hundred languages in these five domains. It does so by mapping to languages a set of 20 indicators, such as GDP per capita, tourist flows and number of speakers, in a coherent and robust way. Each language is ranked for the doors it opens in each domain (labelled ‘geography’, ‘economy’, ‘communication’, ‘knowledge & media’ and ‘diplomacy’). An overall score is derived from these five sub-ranks, with diplomacy given less weight than the first four.

Results

As expected, English is the world’s lingua franca. Mandarin is growing in power but remains a distant second. French comes in third place, with strong results in geography and diplomacy.

Spanish, Arabic and Russian fill in the next three spots. The top six languages – even if the diplomacy opportunity is ignored – also happen to be the official languages of the United Nations.

German and Japanese, the tongues of two economic heavyweights, follow at 7 and 8. The top-ten list of the world’s most powerful languages is rounded out with Portuguese and Hindi, also BRIC languages.

The overall score for each language (second column of the table above) ranges between 0 (least powerful) and 1 (most powerful). With a score of 0.889, English is more than twice as powerful as Mandarin (0.411). However, as China’s economic might and influence grow, could Mandarin one day challenge the supremacy of English? Based on the projected values of the 20 indicators in 2050, English should still be ahead, though by a somewhat smaller margin. The current top ten languages remain in that elite group in 2050, although their relative positions do change.

The PLI assessed 124 languages. The full rankings and methodology can be found here.

Implications for individuals and business leaders

Beyond the thought experiment and fodder for a debate at a bar, the PLI has many implications for individuals, business and political leaders as well as policymakers.

For individuals, language can be a tool for success, and the index provides a guide. The range of benefits depends, inter alia, on the person’s country of origin and native tongue. In mature markets such as English-speaking Canada and United States, studies have shown that learning a second language can yield economic benefits. However, on a macro level, these benefits were mild, considering the time and energy costs. A much better case could be made for people born in developing markets or whose native tongue is less powerful who pick up English or another powerful language. Moreover, the true reward of learning a language is often not economic, but rather cultural and personal.

Native speakers of powerful languages – and even English native speakers who are unfortunately often monolingual – still have many reasons to learn another tongue. A compelling one is that multilinguals have been shown to solve problems more critically. Becoming a polyglot is also about building tools to explore the world and live a fulfilling life. True global citizens should consider gaining functionality in as many languages as they can – indeed, it would be hard to be a global citizen without being multilingual in the world’s most dominant languages.

For business leaders, the PLI gives clues as to the most important languages to implement for a global audience. For instance, what tongues should be prioritised when setting up hotlines, creating websites and translating business materials? Organisers of international events requiring interpreters now have a rational guide on which to base hiring decisions.

Being heard on the global stage

PLI scores show how dominant English is on the global stage. The movers and shakers of the world gain such standing in part by being visible in the most influential media – think interviews, profiles and op-eds in the likes of The New York Times.

Consider the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos. Based on GDP and number of billionaires, Japanese and Chinese leaders are highly under-represented in these and other forums for the so-called global elite. Could the low English proficiency of the Japanese and Chinese be a reason?

The PLI may offer a partial explanation (aside from tax differences) as to why monolingual Tokyo isn’t the financial centre of Asia, despite, in many aspects, dwarfing places such as Hong Kong and Singapore, both of which have deep and historical English infrastructure.

Another case in point: Japan is the second biggest financial backer of the United Nations, yet the Japanese are strikingly under-represented in the upper ranks of the organisation. Japanese is not even an official language of the organisation.

Simply put, the perspective of countries with low English fluency may not be heard at the global level. Without a doubt, there are many fascinating CEOs and leaders who will never be invited to share their ideas on the world stage simply due to their lack of English skills.

English as a double-edged sword

For policymakers, the PLI validates the notion that English confers an undeniable competitive advantage. In the case of countries speaking less powerful languages, promoting English may give their citizens more global opportunities, but at the potential cost of their own tongue losing power or even dying.

At the end of the day, it may be a matter of balance between promoting one’s language and culture (as those are intertwined) and boosting knowledge of English.

Another strategy may consist of embracing global multilingualism. Last year, the Deputy Prime Minister of Kazakhstan recommended that children start learning Mandarin, even as the country continues to implement its decade-old cultural project calling for the widespread adoption of English in addition to Russian and Kazakh. Indeed, in our globalised society, the world is the oyster of the polyglot.

Kai L. Chan is a Distinguished Fellow at INSEAD Innovation & Policy Initiative.

Follow INSEAD Knowledge on Twitter and Facebook.

© 2017 INSEAD Knowledge