A New Global Measure of Gender Progress

A New Global Measure of Gender Progress

Inequality is the “defining issue of our time”, said then U.S. President Barack Obama in 2011 and again in 2013. The next year Pope Francis tweeted that inequality was the root of all social evil. And the IMF issued a report in 2015 framing income inequality as the “defining challenge of our time”.

Where does gender fit in the inequality picture? In most countries, women who want to work face more hurdles than men and, when employed, are often paid less for the same work. Another report by the IMF showed how gender income gaps dampen productivity and growth at the worldwide level.

There’s no question that closing gender gaps – typically understood as giving women equal rights – is a pressing issue. However, I would argue that just as society loses when women fall short, so too when men are stifled.

What Jack can do so can Jill, and vice versa

Take countries like Rwanda, Nicaragua and the Philippines. These countries rank very well on the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Gender Gap Index, a flagship report on the topic. Rwanda, for instance, ranked fifth in the 2016 report because, in terms of statistics, its men are doing horribly considering past wars and the ongoing AIDS epidemic.

It raises the question: If a country wishes to improve its gender equity, should it try to emulate Rwanda? Or, how does a woman born in Nicaragua or the Philippines (also in the top 10 of the WEF Index) actually fare compared with, say, one born in Japan (which ranks 111th)?

Regarding Japan, shouldn’t Japanese men’s extremely high rate of suicide warrant concern, from the standpoint of progress in society?

In short, it’s not enough to look only at where women lag behind men. We should assess equality of opportunity in a more holistic way. Both sexes should have the opportunity to reach their full potential.

A multi-dimensional tool

Launched earlier this year, the Gender Progress Index (GPI) is a multi-dimensional, gender-agnostic tool that was devised to enable policy makers to better understand the problems within society and know where effort should be placed.

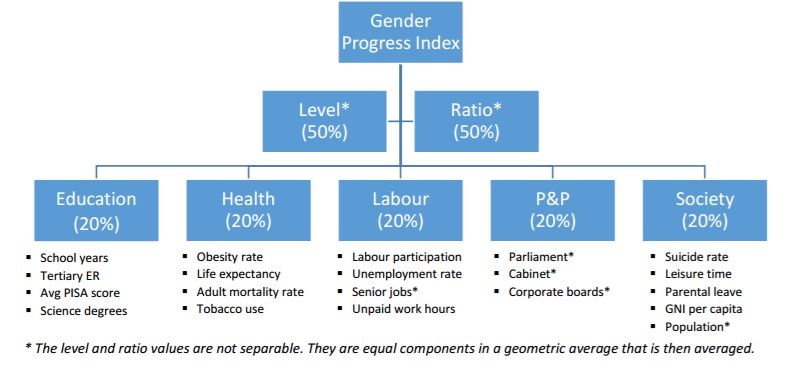

The GPI is based on the following five dimensions, each given equal weight:

1. Education

2. Health

3. Labour

4. Politics & Power

5. Society

As per the chart above, multiple indicators are included within each of the five dimensions. Where possible, care has been taken to select indicators over which policy makers and individuals alike have some degree of control.

The level refers to how the country fares in terms of overall development, while the ratio tracks the corresponding gender gap. Combining development level and gender disparities into one final score allows for fairer comparison between rich and poor countries and makes the index more robust to extreme outcomes.

In addition, neither gender is considered the benchmark: male underperformance is just as detrimental as female underperformance (even as women typically face more hurdles). Scores need to be interpreted in light of a country’s cultural and social DNA. Equality of opportunity is more important than differences in outcomes, so the index also calibrates benchmarks to appropriate channels.

Lastly, the GPI is robust in that a country can’t improve its ranking by eroding an underlying benchmark or leaving behind one gender. For example, in a country where women lag behind men in literacy, a drop in male literacy rate would improve the ratio but regress the level.

The top 10 countries

By simultaneously considering the level of each dimension as well as its fair distribution by gender, the index makes it possible to compare whether it’s better to live in a somewhat equal but poor society (e.g. Cuba), or in a rich but unequal one (e.g. the Gulf countries).

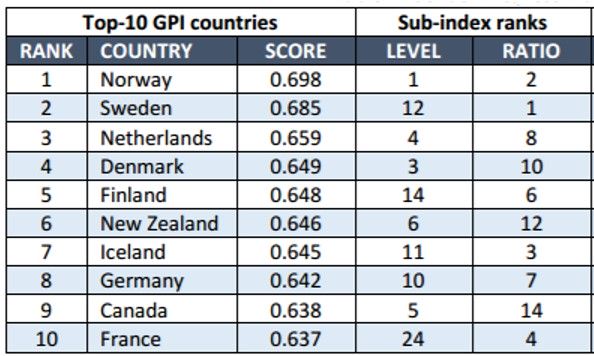

A total of 122 countries were assessed and ranked by level (overall development) and ratio (gender equality). The country with the highest score is Norway. Norway delivers on both high absolute development and gender-balanced development. The index rewards countries that deliver on both and penalises those that are imbalanced in either direction. In fact, the five best performing countries are all from Northern Europe.

The only non-European nations represented in the top 10 are New Zealand (6th) and Canada (9th). Occupying the 10th position, France makes up for a slightly lower level with a strong gender equality ratio, seen especially within its cabinet and corporate boards.

The top-performing non-Western country is Singapore (19th). Costa Rica (29th) is the top country in Latin America, while Tunisia (55th) is the best amongst Arab nations. Ghana (67th) leads sub-Saharan Africa.

The U.S., China and India rank 17th, 28th and 82nd, respectively. It’s interesting to note that China ranks just behind Japan (27th) even though Japan is a much richer society. Mao Zedong once remarked that “women hold up half the sky”, and Chinese data indeed show greater gender equality (vs. Japan) in the Labour, Politics & Power and Society dimensions. Japan is hobbled, in part, by the large number of women who drop out of the workforce after they marry.

Full results, including sub-rankings on the five dimensions, can be found here.

A holistic view of gender progress

The gap in looking (only) at gaps is that policy makers are incentivised solely to raise the performance of the lagging sex (which has always been women in the past) and to stop when “equality” is reached. With a dual perspective on level and ratio – as well as being gender agnostic – policy makers are then incentivised to continuously raise the performance of both genders, yet focus more effort on the lagging sex.

In an increasingly competitive world, no country can afford to waste any human potential. Countries able to design policies promoting the progress of both genders will prosper. It also must be said that no matter the country’s state of development, inequality in its myriad forms can feed resentment and nurture the rise of populism. Getting the best from both sexes harnesses the goodwill of society.

On average, men may face fewer developmental obstacles than women do (and some may even be self-imposed), but a society progresses faster when all its members are able to achieve more. Moreover, policies can have a ripple effect. For instance, programmes targeting a high rate of male tobacco use could also help women stay in the workplace instead of becoming caregivers to a sick husband or other male relative suffering from a tobacco-related illness.

Moreover it’s patronising to always look at gender issues as a case of women lagging behind men. In many countries, women increasingly lead the way on multiple indicators, such as tertiary education. Women should then become the benchmark.

The GPI provides policy makers with a holistic view of gender progress. It factors in both absolute levels of development (the size of the pie) and equality of opportunity (how the pie is shared between genders) across five key dimensions, built upon a large number of meaningful, often practical indicators. Useful policies for the betterment of society can then be crafted with insights based on holistic views of gender development.

Dr Kai L. Chan is a Distinguished Fellow at INSEAD Innovation & Policy Initiative.

Follow INSEAD Knowledge on Twitter and Facebook.

© 2017 INSEAD Knowledge